By Joshua Kato

Moses Musoke has a fairly imposing residence on about a quarter-acre plot on Kulambiro hill, facing Kisaasi trading centre in Kampala.

“The house has six rooms and about 100 iron sheets,” he says.

Musoke later installed a water harvesting system, including valleys and a 10,000-litre water tank to collect rain water.

“When it rains for just 30 minutes, my 10,000-litre tank fills up,” he notes.

Musoke invested around sh2.5m to set up the system after realising that the runoff from his house was causing flooding in the valley below. “

The water that runs down into the valley and floods the road comes from these roofs,” Musoke explains. Unfortunately, most of his neighbours do not have rainwater harvesting systems.

Until about 20 years ago, Kulambiro hill had only a few scattered houses; today, it is entirely covered by concrete, thanks to rapid urbanisation.

Despite this, most of these new buildings do not have proper water harvesting systems. Instead, they direct runoff water onto the newly constructed Kulambiro-Kisaasi ring road, which is now developing potholes.

“Gradually, potholes have started appearing on the tarmac because of this water,” Musoke says.

“If we all harvested this water, the roads would be in better condition, and people living in the valley would not suffer from flooding,” he adds.

It is not just Kulambiro, many buildings lack water harvesting systems and instead direct rain water into the road or drainage.

“Even flats and shopping malls lack water harvesting facilities and have pipes that direct water from the roofs into the nearest road or drainage system,” engineer James Watala says.

Flooding

Most of the roads in Kampala city are in poor condition because of flooding. The water eventually flows towards Lake Victoria, causing flooding not only on its shores, but also affecting other water bodies.

According to the Greater Kampala Drainage Plan, the water flooding the city originates from the several hills that traditionally form Kampala.

For example, floods blocking Jinja Road around Kyambogo come from Mbuya; the water flooding Lugogo originates from Kololo and Naguru hills.

Trapping water

Over the years, all the hills traditionally forming Kampala have been occupied by various types of buildings. Previously, rainwater falling on these hills was absorbed by the soil, with minimal runoff.

“The solution is to ensure that the buildings on these hills have facilities to trap and store rainwater,” Musoke says.

However, while many buildings have pipes and gutters to manage water, it is often directed into drainage systems that run along main roads.

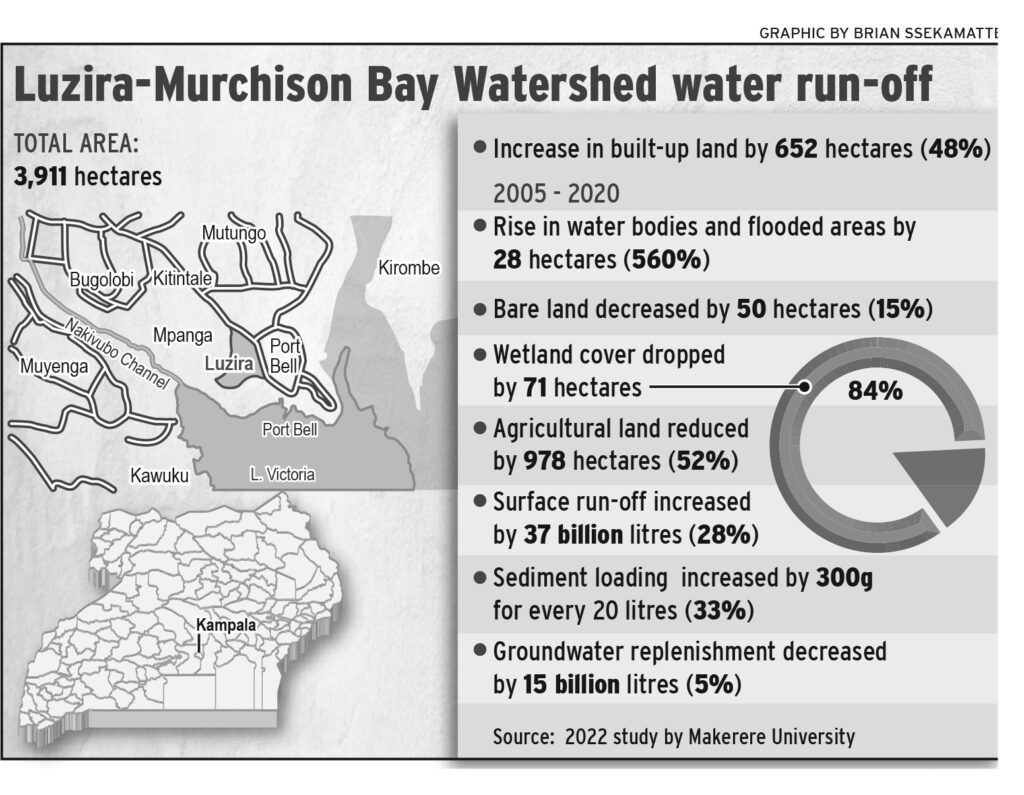

A 2022 study by Makerere University, part of a water security project conducted in East Africa and funded by LASER PULSE, found significant changes in the Luzira-Murchison Bay Watershed.

This watershed which should receive runoff water from Kampala and has a total area of 3,911 hectares, saw an increase in built-up land by 652 hectares (48%), and a rise in water bodies and flooded areas by 28 hectares (560%) between 2005 and 2020.

During the same period, bare land decreased by 50 hectares (15%), wetland cover dropped by 71 hectares (84%), and agricultural land reduced by 978 hectares (52%).

The study also revealed that surface runoff increased by nearly 37 billion litres (28%) from 2005 to 2020, sediment loading (the amount of soil carried in running water) increased by 300 grams for every 20 litres (33%), while groundwater replenishment decreased by at least 15 billion litres (5%).

The study noted, “Reduced infiltration capacity of the ground in the hilly areas leads to increased generation of runoff water that quickly flows into low-lying areas, overtopping the drainage network and increasing the occurrence of flash floods.”

The destruction of wetlands has compromised their ability to control floods, filter effluents, and purify water before it is discharged into Lake Victoria.

The study concluded, “Unsurprisingly, the city faces destructive flooding and flash-flood episodes that have posed severe socio-economic challenges to businesses and residents.”

Ministry action plan

According to the Ministry of Water and Environment’s 2020 Water Security Action and Investment Plan for Greater Kampala, if no action is taken, the risk of flooding will increase by 180% on average by 2040, leading to a significant rise in economic costs associated with floods.

Additionally, water quality will continue to deteriorate, resulting in a 142% increase in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) — the amount of oxygen needed by bacteria to decompose organic matter, thereby reducing the oxygen available for other aquatic life.

Dr Benon Zaake, the commissioner for water resources monitoring and assessment at the Ministry of Water and Environment, explains that rapid urbanisation and improper solid waste management in the Greater Kampala Metropolitan area have exacerbated the flooding problem to the point where existing drainage systems can no longer handle the situation.

According to the International Water Association (IWA), the potential for rainwater harvesting and management (RWHM) to reduce the usage of expensive metered water, alleviate stormwater runoff, and provide drinking water, has been largely neglected in many countries, including Uganda.

This same water can also be useful in urban farming, particularly for vegetable cultivation, thereby improving nutrition.

“For cities and communities to become truly water-wise, leveraging alternative water sources like rainwater is essential. The decentralised nature of RWHM requires the involvement and cooperation of the communities it most affects,” IWA advises.

A water-wise city starts with water-wise communities that understand the benefits of such systems.

“Rooftop rainwater harvesting (RRWH) was identified in the Technology Needs Assessment (TNA) process as a technology with significant potential for climate change adaptation,” the report states.

Rooftop water

Rooftop Rainwater Harvesting Systems offer multiple benefits, including the provision of clean and safe water for domestic use, reduction of excessive runoff which minimises soil erosion, flooding, and damage to infrastructure, as well as providing agricultural irrigation and enabling diversification of livelihood enterprises.

However, only about 0.25% of households practise rooftop rainwater harvesting with adequate storage capacity (6,000 litres) to sustain an average household of six people from one rainy season to the next.

For more details, refer to the RRWH market brief produced by UNEP-CCC as part of the TEMARIN project.

Harvesting involves collecting rainwater from rooftops through gutters and channelling it into a storage container for future use, whether for domestic purposes, crop cultivation, or livestock production.

Rainwater is relatively clean and can be stored in good quality standards for future use.

RRWH is sometimes referred to as Domestic Roof Water Harvesting. The city is estimated to have at least one million houses and commercial structures.

“If just one million houses in Kampala each harvested 6,000 litres of water, this would amount to six billion litres of water removed from the runoff system, significantly reducing flooding,” Water Eng. James Watala says.

Watala advises that although KCCA building construction regulations do not currently mandate water harvesting facilities for every building, they should consider implementing such requirements.

Saving water

James Watala, a water engineer, notes that saving water depends on whether the storage capacity is sufficient for the needs of the household or institution.

The Ministry of Water and Environment recognises tank sizes of 6,000 litres and above as adequate for increasing water access. This estimate assumes up to 90 days without rainfall, an average household size of six people, and water usage of 20 litres per person each day.

To estimate the required storage size, there are four major considerations: demand (number of persons and duration of the dry season) and supply (size of roof surface and amount of rainfall).

Areas with higher annual rainfall can harvest more and, therefore, need larger tanks compared to dry areas. Additionally, households with larger roofs can collect larger amounts of rainwater.

Watala explains that a household of six people pays approximately sh60,000 per month for piped water, totalling around sh720,000 per year.

Installing a 10,000-litre tank costs about sh1.8 million, with additional costs of sh200,000 for guttering, sh200,000 for a stand, and sh100,000 for pipework and fixtures. The system can last over 20 years.